How you can be Younger Next Year

We all expect to get older and slow down.

We avoid stairs, have our chiropractor on speed dial and exercise is something we used to do. It’s a predictable downward slide that eventually finds us slumped in a lazy-boy, sipping lukewarm beer watching NBA playoffs.

No thanks.

Enter younger next year

When Chris Crowley sat down the first time with gerontologist Henry Lodge it was to get fixed. Crowley had recently retired from his busy law practice and wanted quick solutions for getting his health back and losing a few pounds.

What he discovered was something quite different—a new way to think about health, aging, and, yes, losing weight.

It turns out reversing unwanted results of years of bad habits was not only possible it was surprisingly simple. It only took two things to make happen.

Commitment and consistency

Over the next few years, the gregarious Crowley teamed up with more scientific Lodge to piece together a very readable primer on how to age well. Their first book Younger Next Year leaped to the best-seller list and spawned a series of other Younger Next Year books.

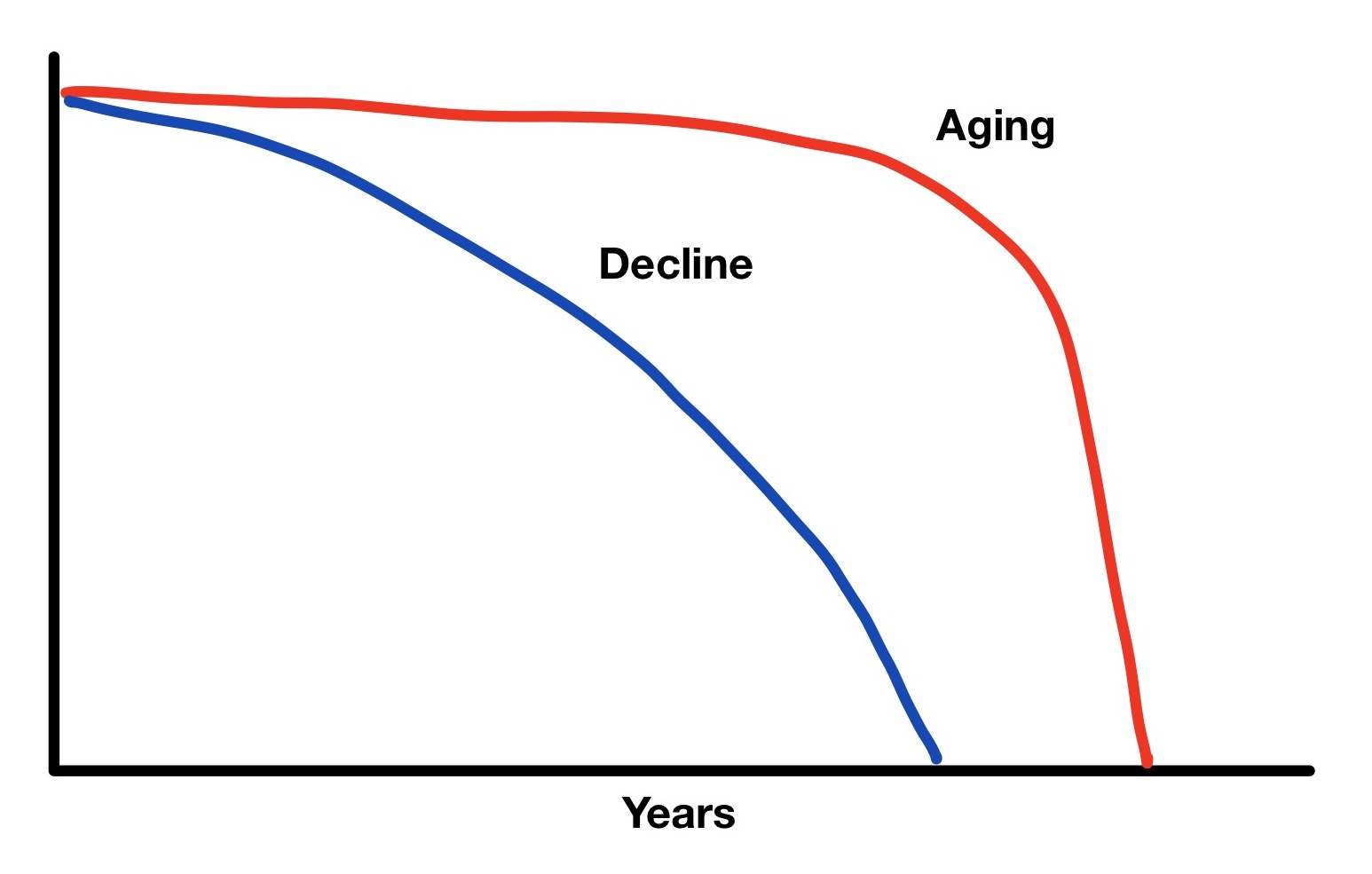

The central theme of all the Younger Next Year books is simple: avoid decline.

Avoid decline

If you want to enjoy a healthy life with lots of energy and the freedom that comes from being physically strong you need to resist the gradual, debilitating pit of decline so many people fall into.

This is how Crowley describes typical aging: “Every year a little fatter, slower, weaker, more pain-racked. Your teeth are bad yellow, and your breath isn’t so great, either. You don’t have any money. Or hair. And your muscles look like drapery. You give up. You sit there and wait. Go to the Nursing Home…get tied to a chair.”

It’s nasty stuff.

Instead, you need to be more like my mother.

My mother was born into a time of war, disease, death, and the kind of resiliency so often expressed after hardship. Born in Halifax, just six months after the explosion that leveled half the City, her world was reeling from the devastation of the Great War and the Spanish Influenza.

My mother’s infectious pollyanna outlook on life came to her honestly. Her generation - future parents of baby boomers - grew up in a world rebuilding with wide-eye hope for a better future.

My mother’s infectious pollyanna outlook on life came to her honestly. Her generation - future parents of baby boomers - grew up in a world rebuilding with wide-eye hope for a better future.

As a young woman, she volunteered with the Red Cross, and after returning from serving overseas followed my father West to start her own family.

She walked every day, preferred good books over “watching the tube”, and was self-taught in pottery, dying and spinning wool, and loom-weaving. Her life was full, regrets were few, and a few weeks short of her 89th birthday she took ill, retired to the local hospice, and within two weeks moved on.

Her life was a case study of what Lodge refers to as a hunt-and-hibernate approach to life.

Hunt and hibernate

Car manufacturers have a neat trick they’ve been playing on us for decades. Instead of starting from scratch every time they update a car or truck model, they build the fancy “all new” model on top of the old chassis. For example, the ubiquitous Ford F-150 has had many new models over the years, but the chassis rarely changed.

Our bodies are no different.

Our chassis (the brain, heart, bones, organs, intestines, muscles, etc) aren’t much different from our distant Palaeozoic age ancestors. Sure, we have an iPhone in our pocket and scan menus for gluten-free options, but our body's response to stress and rest hasn’t changed much for millennia.

Central to how we respond is our design to hunt and hibernate.

When we exercise we’re hunting. Hunting is good. That’s when our muscles are stressed, breaking down, and getting rebuilt. Hunting stimulates healthy disease-fighting white blood cells attacking bacteria, viruses, inflammation, cancer cells, and all sorts of nasties - a process called autophagy (see note).

When we hibernate (sitting, reading a book, sleeping, watching TV, or writing) the body stores fat. Hibernation is good…in moderation. When our ancestors hibernated it meant winter must be coming or times were tough. When we hibernate we also load up.

In Younger Next Year, Lodge promotes a daily balance between “hunting” with physical exercise and “hibernating” with rest and relaxation. Repeating this cycle is like giving your chassis a tune-up. Your body becomes stronger and more resilient while the stress hormone Cortisol is replaced with feel-good endorphins and Dopamine.

Recent research into high-intensity interval training (HIIT) proves that duration is not as important as intensity. The secret to good “hunting time” is to raise your heart rate.

Get more beats

The benefits of autophagy and exercise happen when you introduce stress to your body. Walking is beneficial in other ways, but health-improving exercise is all about short-term stress.

When you raise your heart rate you’re exercising your heart, building oxygen-carrying blood capacity, burning fat, and building muscle. That magical cycle only kicks in when you reach 60-65% of your maximum heart rate (see notes). With regular, endurance-style exercise (running, cycling, swimming) your goal should be 30-60 minutes a day. Even less with High-Intensity training.

It’s not a sprint

I have always been a last-minute athlete. When a big competition got near I would go like a madman compressing what should have been months of training into the last few weeks. That’s a trick I could pull off in my 20’s and 30’s.

Today I need consistency and variety (I wrote about procrastinating about exercise in this post.)

My goal is an average of one hour of exercise every day. On days when I’m travelling the best I can do is a 15-minute hotel room workout. But my average is always 30 or more hours a month of exercise at an elevated heart rate.

Somedays I’m logging a 45-minute walk with my dog, on others I’m at the gym, distance training in an outrigger canoe, or running the trails near my house.

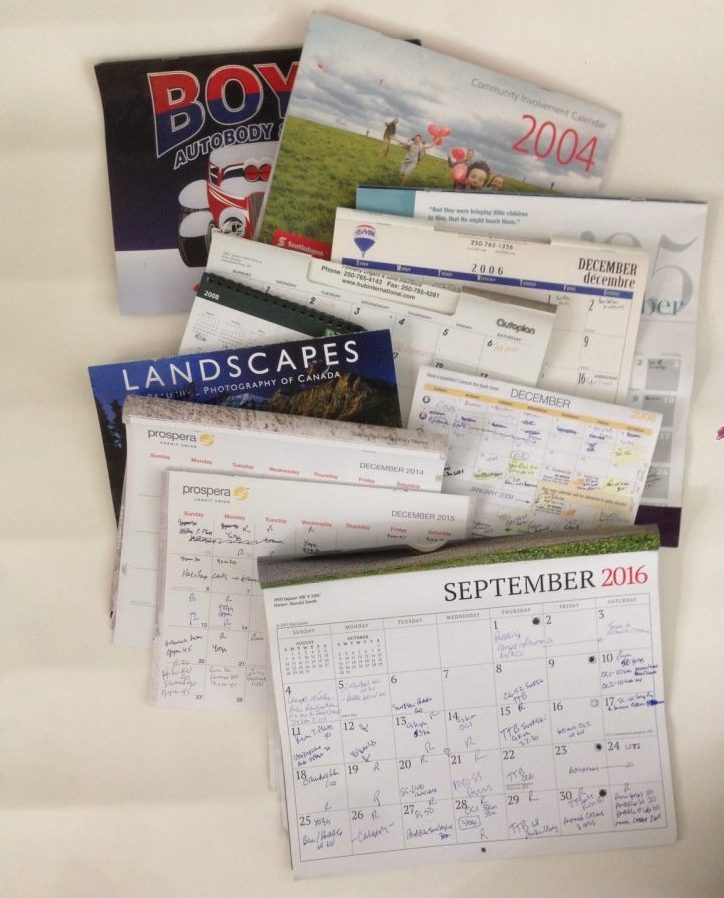

For motivation, I log all my workouts on a calendar. I have calendars going back 20 years. As obsessive as that might seem, the act of pulling out the dog-eared calendar at the end of the day to record my workouts is a big motivator. Every entry is a reminder that I had the willpower to overcome resistance and get the work done.

Now, let’s deal with resistance.

Anytime is a good time

According to Crowley and Lodge, it’s never too late to regain balance, coordination, muscle, and aerobic capacity. “Most aging,” wrote Lodge, “is just the dry rot we program into our cells by sedentary living, junk food, and stress.”

In a five-year study of 10,000 men (hard to argue with those numbers), the fittest had one-third the mortality rate of the rest. But here’s the great news – the guys that got fit during the study dropped their mortality rate by 50%!

As an example, Crowley, who’s now in his 70’s and still enjoys daily hard-core workouts, didn’t start turning his health around until his 50’s.

This is important: your body is ready to respond to what you throw at it. Sure you might be sore after your first bike ride or first visit to the gym in 20 years. That just means your body is working – doing what it was designed to do – replacing old cells, adding muscle, and burning calories.

The way to get started is to first reduce friction.

Reduce friction

Choose an activity you can maintain every day, like walking, yoga, meditation, or cycling. And then choose the diet change you can keep every day, like drinking water in the morning, cutting back on coffee and alcohol, or reducing consumption of anything white (pasta, bread, muffins, potatoes).

If you look at what you tried to change but quit in the past, it probably failed because it wasn’t convenient.

Let’s start with something convenient, like walking, and why it might be a waste of time (the way you’re doing it now).

It wasn’t until I read Younger Next Year that I realized I was missing out. With a little more effort, I’ve been able to turn my walks into a workout. Here’s how it works.

The good news is the solution is simple. In fact, it needs to be simple and convenient or it’s not likely to last.

The solution is simple

Daily medicine

Build exercise into every day. Here are some simple, convenient ways to get started:

Get up 15 minutes earlier and go for a brisk walk right after your first cup of coffee. Don’t debate it: stack your new walking habit on top of your coffee habit (rain or shine).

Park two blocks further from your office and walk to work.

Move your recycling box, garbage can, and water bottle away from your desk (even your printer) so you have to stand up to use them (this strategy is highly recommended by researchers who study the dangers of excessive sitting).

Build a habit of standing for phone calls or conference calls and taking short standing/walking breaks throughout your day. Aim for standing and moving at least every 30 minutes.

Three times a week download a favorite podcast and take in a brisk 30-minute walk or cycle right after work.

Drink a glass of water before meals so you’re less likely to overeat. Also waiting 20 minutes before getting seconds gives your body time to register how full you feel.

None of these are a big deal—you can easily work them into your day without much sacrifice, but the results will be huge.

Like magic, you are becoming a stronger person in body and in mind. And that’s healthy.

If you liked this post, here are some more about health:

Aging vs. Decay – how to stay healthy, wise and sexy as you grow old

5 Foolproof Tips for Staying Healthy as a Road Warrior

You already have what you need (money, time, health and sex)

Feature pic byphoto nic onUnsplash

Notes:

According to the Cleveland Clinic: Autophagy is your body’s cellular recycling system. It allows a cell to disassemble its junk parts and repurpose the salvageable bits and pieces into new, usable cell parts. A cell can discard the parts it doesn’t need.

You can calculate your maximum heart rate by subtracting your age from 220 (medical experts will roll their eyes at this crude math, but for most of us it’s a good place to start.) For me, that is 220-65 = 155 BPM (beats per minute.) So a good, steady workout for me would be: 155 X .65 = 101 BPM.

Small Wins - Why Little Steps are the Path to Big Rewards

Keynotes and workshops by Hugh Culver